From Kenyan drama to Thai horror - how far has smartphone filmmaking come in amplifying marginalised voices?

Smartphones have changed how we make and consume media in our daily lives. But how have they impacted the film industry globally?

Written by Jess Sweetman

Just as digital filmmaking and DVD distribution did before it, mobile technology promised to radically change how we consume and create media across the world. In some ways, we are already witnessing seismic social change promised on a global scale - from Black Lives Matter to the Arab Spring, from TikTok fads to call-out culture.

In this article we’re going to dip toes into a few of the places where smartphone filmmaking has made an impact, building cottage film industries, giving voices to ignored populations, and training a new generation of creative filmmakers in a few corners of the world.

Smartphone filmmaking across Africa - building and training

According to the 2021 UNESCO report The African Film Industry: Trends, Challenges, and Opportunities for Growth: “Perhaps the most encouraging trend of the last decade has been the slow but steady rise in the volume of production across the (African) continent…A few factors explain this phenomenon (including) the digital revolution, which is making audiovisual content cheaper to produce and easier to distribute.”

UNESCO lists Kenya, Rwanda, Ethiopia and Senegal among African markets where a new generation of creators is able to live from online revenues generated by their films, and according to a report by the Botho Group. The Côte d'Ivoire, is also in on the action, hosting the African International Smartphone Film Festival.

The impact of mobile phones in Kenya is documented to have wrought a lot of social and economic changes that the country now dubs itself “the silicon Savannah” - bringing with it a cultural shift from communities gathering in one space to watch terrestrial television, to individuals streaming media on smartphones. In addition, according to the UNESCO report: “Social media is increasingly becoming a valid source of revenue for Kenyan creators, with many of them now opting to distribute their content online rather than selling it to traditional broadcasters. In January 2021, YouTube announced the 20 winners of its inaugural Black Voices Creators Class, which included four Kenyans.”

In Somalia, young filmmakers have gained the world’s attention for using mobile phones to create video content for online streaming.

The cottage film industry in Rwanda, which was previously decimated by war, has also seen a generation training and making an income through smartphone productions - focusing mainly on soap operas, comedies, and series’, rather than films. According to Unesco: “The most notable development in the video space has been the rise of YouTube as a sustainable source of revenue for Rwandan producers, who have also found online the freedom to create more innovative content.”

But while individuals or groups are resting content for online streaming, what of more traditional filmmaking?

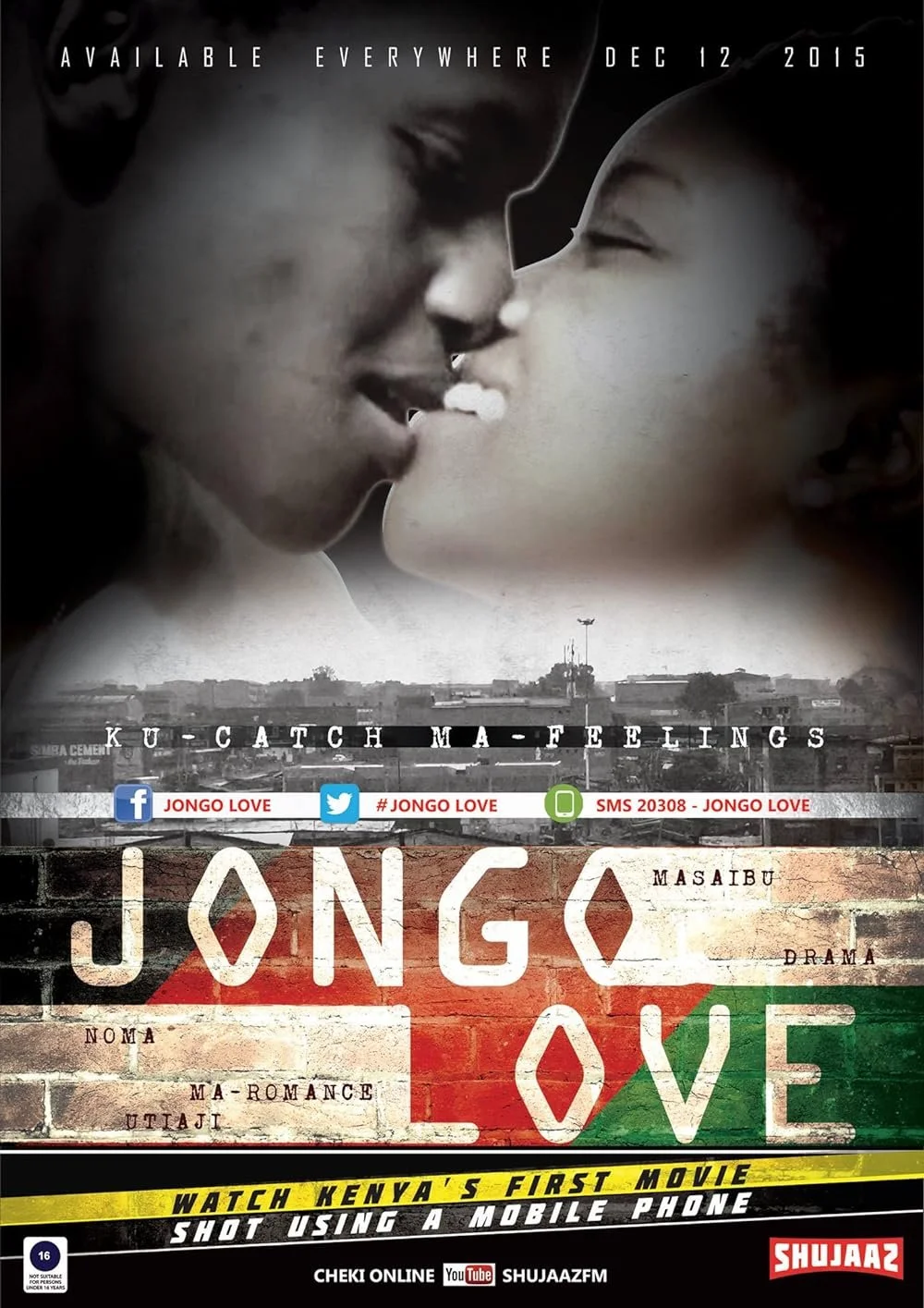

In Kenya, according to The Guardian: “While auteur filmmakers are reaching a global audience through the film festival circuit, Kenya’s home film industry relies more heavily on low-budget filmmaking and distribution. For example: “ Jongo Love”, a love story and thriller released in Kenya last December, was shot entirely on a Nokia Lumia 1020. “

The South-African comedy-drama “High Fantasy” was “shot in a found-footage style by using multiple smartphones. It was premiered at Toronto International Film Festival and Berlinale in 2018.”

Even in Nigeria, home of the second-largest film industry in the world in terms of output, smartphone filmmaking is enabling the next generation of talents to learn their craft and move the industry forward as a whole. A group who recently hit the global news were The Critics - a group of Nigerian young filmmakers whose mobile phone films featured impressive amounts of VFX.

The arthouse is no stranger to smartphones

The arthouse film world is no stranger to eschewing traditional camera set-ups - from direct on film animation styles explored by filmmakers Len Lye and Norman McLaren, to the montage storytelling from the Left Bank Movement of La Jetee (Chris Marker) or Robert Downey Sr’s 1966 parody experimental film “Chafed Elbows”, via the single blue frame of Derek Jarman’s final film “Blue” (1993). The freeing from form allows the artist to give voice to criticism, pain, or explore the world around them in a different way.

As such smartphone filmmaking fit right in: One example is the 2007 film from Dutch filmmaker Cyrus Frisch: “WHY DIDN’T ANYBODY TELL ME IT WOULD BECOME THIS BAD IN AFGHANISTAN”, which used the grainy mobile phone footage to express the anguish of a soldier who has returned from war-torn Afghanistan with a new vision of the world.

In many ways mobile filmmaking in this manner continues an arthouse and conceptual art film tradition of using filmmaking methods away from traditional cameras.

Voices of the Oppressed: Documentary filmmaking in the age of smartphones

“This Is Not A Film” is a documentary by the Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi, which was made during and about his life under house arrest, while he was also banned by the Iranian regime from making films. The film was smuggled out of the country in a cake and screened at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival to acclaim. Critic A. O. Scott of The New York Times called “This is Not a Film” a "brave and witty video diary, an essay on the struggle between political tyranny and the creative imagination."

The convenience of cameraphone has also allowed refugee groups and other traditionally voiceless people the ability to share their lives with international audiences. The documentary “Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time” - was shot on mobile phone from filmmakers resident in a refugee camp outside Australia - the Manus and Naru detention centres.

Another example are the feature documentaries “MyEscape” and “The War on My Phone” by Berlin-based director Elke Sasse. The former compiles mobile phone footage of refugees escaping their homes and the latter gives an intimate insight into the everyday lives of Syrian friends and families separated by the civil war.

I caught up with the director to ask her opinion on the impact that smartphone filmmaking has had on her subjects: “Using mobile phone material for me is a way to document realities I wouldn’t be able to document otherwise and to use videos filmed in a very personal perspective” But the director still offers a warning: “I would only use mobile phones if there is a reason. If you can’t use professional equipment – because it is a place where professionals can’t go, because you want a very personal perspective, if you have a reason to choose this kind of aesthetics, and so on.”

Check out the full interview with Elke Sasse on our Industry blog.

Smartphones in Horror

Similarly to the arthouse circuit, horror audiences have a rich history of choosing good scripts, relatable characters, and - naturally - good scares over high production costs, making this another genre that lends itself to the potentials of mobile phone filmmaking.

Horror cinema was always bound to embrace the freedom of mobile phone footage. Since the 90’s, found footage horror films have grabbed an audience of horror fans - starting with American films “The Last Broadcast” and “The Blair Witch Project”, but also making space for films from other countries, such as the Spanish horror film “Rec” leading to a universe of knock-offs and reboots.

It is probably unsurprising that a genre that prefers authenticity to sleek and expensive-looking filmmaking would expand to embrace mobile phone (and even webcam) filmmaking. The most 2016 “Blair Witch” reboot showed off phone cameras, GoPros, and drones. Add a pandemic on top of the technological revolution and we get films such as the British supernatural horror film “Host”, which takes place in 2020 during a Zoom seance - which was filmed during the COVID pandemic and provides a perfect snapshot of the time told in a horror film.

In the 90’s, the digital revolution in filming and DVD distribution led to the worldwide popularity of Japanese and South Korean horror films globally. And in some ways, the streaming phenomenon has brought more global attention for horror from South East Asia - in countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines - each with its own growing film industry. The filmmaking from these countries, while deeply influenced by the affordability and convenience of digital filmmaking, seems to mostly have resisted the “found footage” trend, which lends itself to mobile phone filmmaking.

According to film theorist Katarzyna Ancuta’s exploration of found footage horror films in Southeast Asia: “Although recent productions reflect significant efforts to modernize the genre and make it more appealing to the urban middle classes, who constitute the largest group of consumers of media products in the region, the hold local supernatural folklore has on Southeast Asian horror films remains strong.”

But there are rare examples of phone-filmed horror films in Southeast Asia: “Those That Follow”, a Thai horror short directed by Parkpoom Wongpoom is one of them. The film was shot entirely on an iPhone 13 Pro and is described as a “hallucinatory tale of karmic revenge” …The director filmed in low-light conditions using the Apple iPhone 13 Pro, which can shoot in Dolby Vision up to 4K at 60 fps 1).

Japanese and South Korean horror films have also taken up the “found-footage” mantle on occasion, using mobile phones to create their works, such as the Japanese-produced and made by a South Korean director “Paranormal Activity 2: Tokyo Night”, and 2010’s “Shirome”. In addition the 2011 South Korean horror short “Night Fishing” by Park Chan-wook and Park Chan-kyong was shot on Smartphones by the celebrated directors.

In Conclusion:

Mobile phone cameras have changed how we see ourselves and have led to huge structural change, how we consume media is different, the kinds of videos we see are also very different to previous, but when it comes to more traditional filmmaking it’s still unlikely that a feature film you see at a festival will have been shot on a Iphone - for now.

The impact of more and more people having a camera in their pocket, however, continues to impact the paths of people into the film industry, widening it beyond the traditional lines.

In addition, documentary makers can reach subjects who would be otherwise out of reach, or where countries with new and booming industries can create income streams for their creators.

Cameraphones have allowed subgenres within horror to stretch a little, as well as fuelling a change in how we watch media - but traditional film, with its emphasis on quality production values, has remained mostly unchanged - at least for now.